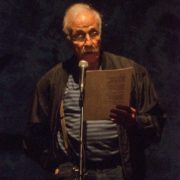

The Brokenness of Things

Hello friends. How often we carry the ideas received from our parents into our own adulthood, especially regarding family. “You’re just like your father,” Ma used to say to George when he displeased her. It’s interesting how good and bad roles, repeatedly prescribed by parents, become durable markers of personality. We tend to live up to these given roles. No one begins life with a clean slate, a tabula rasa. Only later, of course, did I realize how immersed I was in an ethnic Italian-American culture.

Even later when George became a lawyer and president of the Hibernia Bank in San Francisco, my mother could not give up the habit of comparing her sons negatively to the good boys in the neighborhood. She was very short on any compliments to us, except when we were “very, very good.” Are things ever perfect? No. In many ways we come to love and, hopefully, forgive the brokenness of things where there are no real answers, only more questions.

The Brokenness of Things

I was shocked to hear of my brother

George’s stage-four cancer at eighty-two.

So many conflicted thoughts and feelings:

with sadness for him and failure to achieve

closer friendship as we found ourselves

drifting apart in worldview when growing older.

Levels of adult success didn’t matter that much:

a priest-professor and a bank president.

He drifted right in politics and economics,

like many college-educated, immigrant Catholics.

I went left, as a progressive Jesuit and democrat,

driven by the social gospel after Vatican II.

He was more tormented by anger though

we both suffered marital break-ups.

He was more like our father, Gino,

fighting hidden ghosts of war and other threats

but steadfast in support of family.

I was Katie’s boy, doing right until I didn’t.

Yet she made peace with me, the married priest,

ever kindly, even until my last good union.

Perhaps the blighted treasure of the professor

is a compulsion to figure it all out

instead of making peace

with the brokenness of things.