REVIEW: The Religious Experience Of Revolutionaries, Eugene C. Bianchi [1972]

REVIEW

The Religious Experience Of Revolutionaries

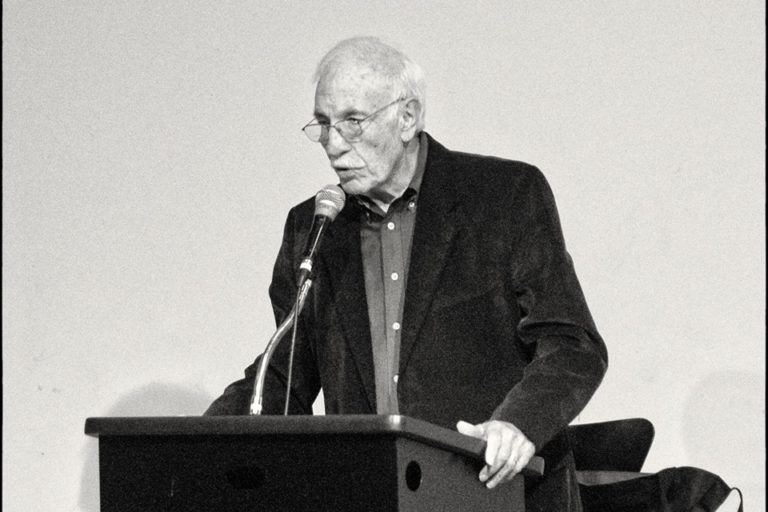

Eugene C. Bianchi

By Will Davison

To look for the religious experience common to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., D.D., the Rev. Daniel Berrigan, S.J., and even Malcolm X is a reasonable venture. Add revolutionaries like Abbie Hoffman, Che Guevara and Frantz Fanon, though, and it would seem that chances of the search’s success are slim. Eugene C. Bianchi attempts here to show that he has succeeded.

Early on, the reader is disabused of the idea that true religious experience today is anything like the faith of our fathers: “The religious experience can be found in its deepest dimensions within the secular experience…. I am affirming that the secular experience is not to be reduced to a traditionally religious (Christian, Muslim, Jewish) meaning or symbolization.”

Oviously no ready‐made definition can describe the religious experience of these clergymen, doctors and hustlers, a black and a white each, all born in the twenties and all turned revolutionaries. “The religious experience,” then, according to Bianchi, “is the secular experience of self‐transcendence toward freedom in community.” It is by this formula that the religious experience of each man is painstakingly evaluated.

In two chapters, a quarter of the book, Bianchi spells out guidelines for exploring revolutionary religiousness and puts forth his reflections on dissenting spirituality. He sets up a series of scholarly, dialectical, mobile hurdles over which the revolutionaries are obliged (reluctantly at times, it seems) to jump. Guevara was an avowed atheist, but Bianchi assures us that he didn’t behave very much differently from someone who believes in God. When Berrigan and King said they believed in God, they really meant, interprets Bianchi, they believed in Guevara’s New People or Fanon’s New Humanity.

Although Hoffman has behaved illegally and defied social canons, we must remind ourselves, counsels Bianchi, “the anarchist construes his morality on a different primordial principle than that undergirding conventional morality.” Fanon glorified violence, but do you know that “Simone de Beauvoir remarked at Fanon’s own sense of repulsion from the horror of the killing in North Africa”? What sort of nonsense is this? It is almost as if Bianchi, were intent on gratuitously leading these six revolutionaries in search of character.

Bianchi has little or nothing new to tell us about his revolutionaries, to each of whom he devotes an essay‐like chapter (lecture?). What purpose does the book serve? The reader finds himself wondering frequently who is speaking—the revolutionary or the author.

For example, Berrigan is ‘’a natural scapegoat for the hawkish Cardinal Spellman”; Hoffman “wants to carry flowers into St. Patrick’s Cathedral protest against a hawkish cardinal.” Again, Berrigan “saw America confronted with the incredible phenomenon of the white Westerner who hired blacks to kill Orientals and be killed protecting the white man’s interests.”

One might be inclined to regard this ivory‐tower philosophy of revolution as purely academic. Carry it to its logical conclusions, however, and there is danger. Who would suspect that in a book titled “The Religious Experience of Revotionaries” there is justification for the massacre at Lod Airport by Japanese gunmen engaged by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and for the slaughter by the Black September Movement of 11 Israelis at the Olympics? Many statements justify exactly this kind of anarchism and violence. One quotation will suffice (and this is Bianchi speaking): “From a moral perspective, Fanon’s advocacy of violence can be justified as an exercise of self‐defense and liberation from a tyrannical colonial situation.”

Fanon is an intellectual hero of radical Arab guerrillas. This is not an easy book read—perhaps fortunately. its style is redolent of the mind-boggling, tortuous syntax peculiar to such monumental works as Niebuhr’s two‐volume “Nature and Destiny of Man,” Tillich’s three‐volume “Systematic Theology” and Barth’s multivolume “Church Dogmatics.” Not exactly campfire reading for revolutionaries!

The New York Times, November 5, 1972, Section BR, Page 20